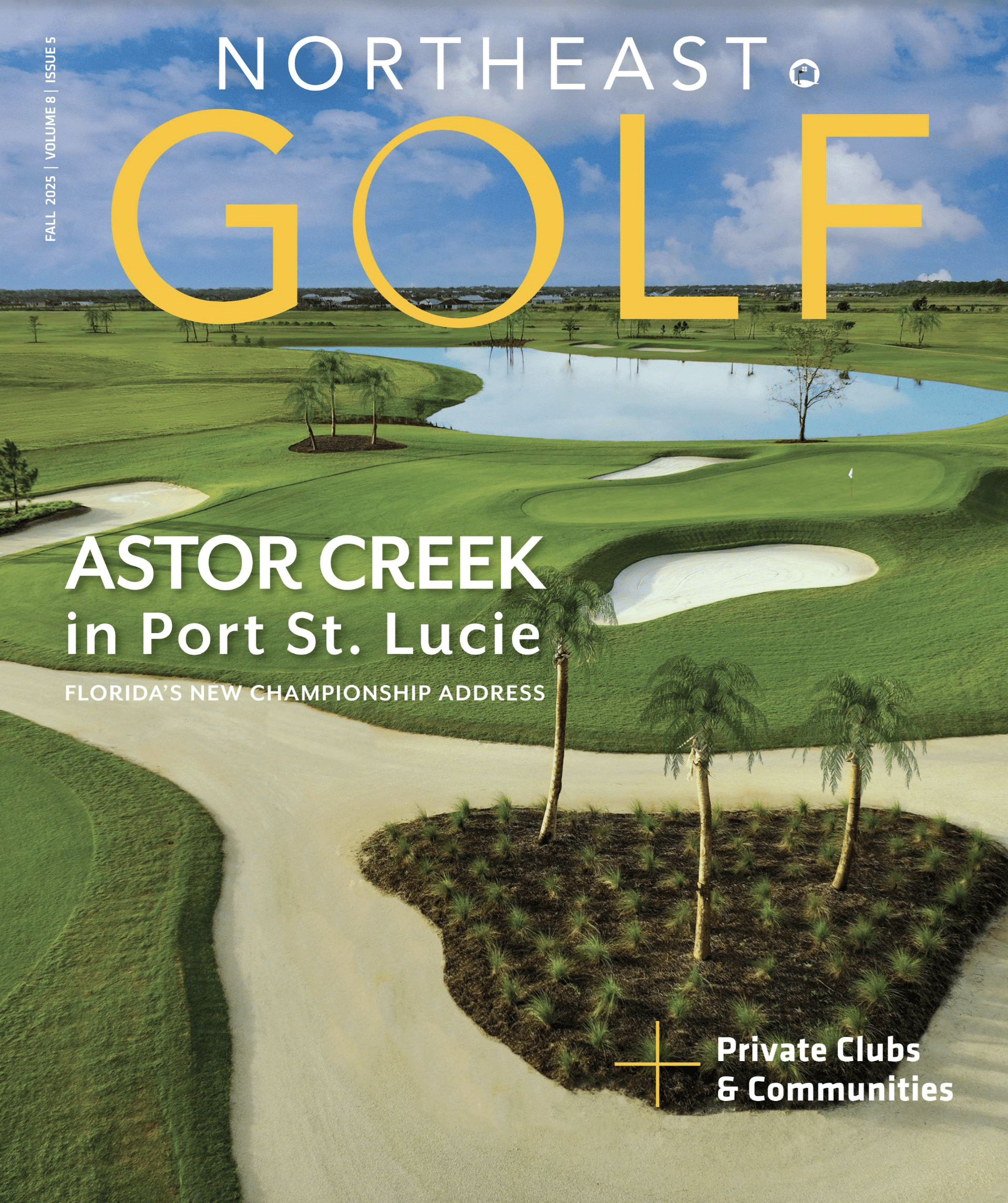

OAK BLUFFS, Mass. — Farm Neck Golf Club here on Martha’s Vineyard has reopened following an extensive, unifying renovation from architect Mark Mungeam, whose work better accentuates and refines the property’s sandy, seaside environs while opening up long views over the salt-water Sengekontacket Pond.

“It’s no secret that the two nines at Farm Neck were rather dissimilar, as they were built by different architects, five years apart,” says Mungeam, ASGCA, who’s been consulting to Farm Neck GC for more than 20 years; he refashioned all 18 greens in 2012-13. “We agreed it was high time we bit the bullet, cut back the forest obscuring the ocean views, and replaced it with vegetation and dunes features indigenous to the island.

“At the same time, we’ve added more fairway turf out there — nearly all of it in widening the playing corridors. Farm Neck has always been one of the most picturesque courses in the country, in part because it’s a unique hybrid design on sandy, coastal terrain. That aesthetic we wouldn’t dare touch. In fact, we’ve doubled down by accenting each hole with sand and native grasses at the edges.”

While formalized golf has been played on this property since 1897, the first nine at Farm Neck GC opened in 1976. Designed by Mungeam’s former partner and mentor, the late Geoffrey Cornish, this original loop was joined by another, designed by Patrick Mulligan, in 1980. The combined 18 was quickly hailed as that rare bird: a seaside, resort course every bit the aesthetic equal of any private club.

Farm Neck is, in fact, a semi-private club with a diverse and vibrant membership. In the U.K. style, the public is welcome all year round, even if members tend to make tee times rather scarce in July and August.

“It gets pretty crazy here in high summer,” attests General Manager Tim Sweet. “But most of the members will tell you: Martha’s Vineyard is truly glorious in the shoulder seasons. It’s unhurried and uncrowded in May and June. The golf course goes technicolor in September and October. We routinely play here through Thanksgiving and beyond. It’s also worth mentioning that accommodations out here are far more reasonable off season.

“Golfers understand the balance that must be struck in resort areas like this one. The club is committed to optimizing that balance, as evidenced by our investment in this renovation. Mark did a spectacular job. I’ve been here almost 50 years and the course has never looked or played this good.”

Mungeam’s refurbishment was both comprehensive and inventive. Hundreds of miniature “Cape” pines were removed, most of them replaced with native areas that maximize playing width and vistas. All 18 tees were rebuilt and the entire layout effectively rebunkered. The course used to feature 91 formal bunkers. While that total has been reduced by a third, golfers will nevertheless experience far more sand. And scrub.

The best example of this dynamic may be the 3rd and 5th holes, which had been separated dozens of pine that had slowly overtaken a former sand pit. They’re all gone, replaced by 120 yards of flamboyantly contoured, informal bunkering festooned with erosion-controlling, native vegetation. Such artful clearing also means the dramatic, picturesque 4th — a par-3 playing down to the shores of Sengekontacket Pond (made famous by the movie, “Jaws”) — can now be enjoyed by golfers on all three holes.

“The native area between 3 and 5 is the look we used to pull the two nines together stylistically,” explains Mungeam, who will take the gavel as president of the American Society of Golf Course Architects in October. “We created the same shared, sand-and-scrub features between the 11th, 12th and 16th holes, for example. Between 17 green and 18 tee, too.”

Sweet and Mungeam singled out contractor Matt Staffieri for his valuable input in fashioning these naturalized areas. His firm, Hopkinton, Mass.-based MAS Golf Construction, rebuilt the front nine from autumn 2023 to spring 2024, then the back nine from October 2024 to May 2025. Superintendent Andrew Nisbet, assistant Ryan Carey and their crew also played key collaborative roles in creating Farm Neck’s newly cohesive, naturalistic presentation.

“Folks like to talk about making things that are more sustainable, but working on an island requires more than talk,” the architect says. “Bringing sod to Farm Neck requires cutting it somewhere, shipping it by truck to Wareham, offloading it to another truck, then bringing that vehicle across on the ferry. That’s expensive and it uses a huge amount of energy.

“At Farm Neck, we significantly reduced our sod imports by ‘flipping’ existing turf. This is a big property, some 425 acres in all. We would identify native grasses along the edges of the course, remove it with a sod cutter, roll it up where we could, put it on carts and move it to these new naturalized areas. We also saved and re-deployed every last bit of fescue and bluestem from areas disrupted by the renovation. When we rebuilt the tees, we saved that bentgrass and used it to expand the fairways — maybe 10 acres’ worth.

“People ask me what native grasses we used to build these new areas. I don’t even know! There’s a lot of fescue and little blue stem — the rest we’d need a botanist to identify. But it’s native. We found it growing on site, so we know it will thrive here. Of late, the state of Massachusetts has also been very encouraging when it comes to restoring what it calls ‘sand-plain grassland habitat.’ That is exactly what we’ve done here.”

Some of those grasses, along with the attractively sandy soil, are exactly what lured the ancients to this property 130 years ago. According to Farm Neck grounds committee chair and club historian Jonas Peter Akins, the Cottage City Golf Club opened for play in 1897, on this very property, mainly on what is today the back nine. By 1901, the prolific Scots architect Alex Findlay had expanded CCGC to 18 holes.

That August of 1901, the magazine Golf and Lawn Tennis reported: The first thing that strikes the eye on reaching the course is the sea, that bounds a number of the holes; then… sand pits, for the most part natural, marshes, small ponds, rushes and coarse grass forming splendid hazards.

“I think that’s a lot closer to where we are today, as a golf course, compared to 5 years ago,” says Akins, who notes that CCGC underwent serial name changes and financial difficulties before being abandoned in the early 1970s. “If you squint, you can still make out several former hole corridors on the back nine. But I love the fact that native grasses — that have been growing on and around those old holes for 130 years — are again an integral, natural feature at Farm Neck.”

Learn more at https://www.farmneck.net/.